A common anecdote—not even an anecdote, really, just a moment bolted to the temporal ground in my personal development—I bring up when discussing my ideological inclinations is from the first few months of university. On a bulletin board on campus was a simple poster advertising jobs for quick cash—selling steak knives over the phone. The poster had tabs at the bottom with a phone number to call to inquire. I asked myself (not the contact at that phone number; I did not take a tab): what good does that do? What’s the purpose? Steak knives are available at any store with a housewares department. People usually only need one set, and they (should) last a long time. How do we have an industry that can profit from this?

I was 18, but not that naïve. I knew the answer: predatory marketing. Not just to the customer—this recruitment tactic was also clearly preying on young workers in the process of racking up debt. But there was no purpose, no improvement to anyone’s lives from this economic activity. I was already leaning left (and this was a left-leaning university); this experience served as an anchor in my memory for framing perspective as I further grew into the world around me.

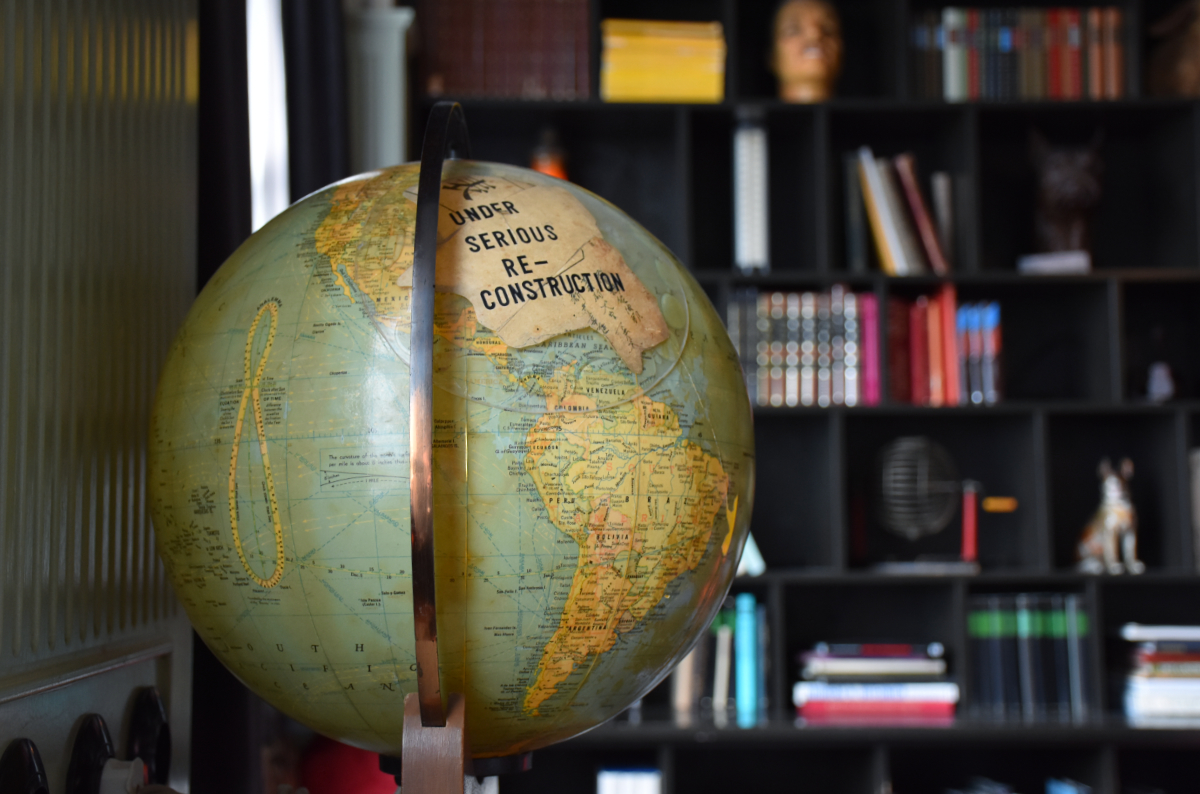

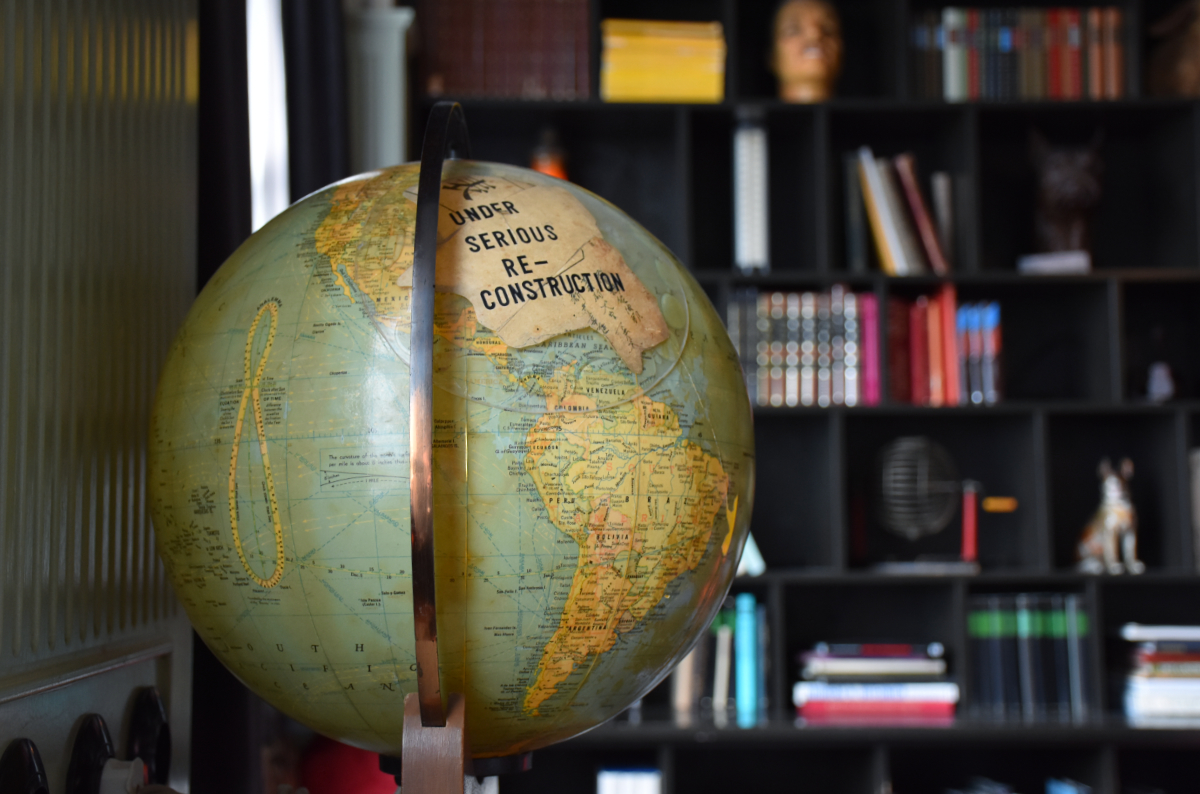

As a sociology student I learned to examine this world as formed by past choices, bu a mix of collective decisions and individual ideas. Powerful people made decisions to establish institutions; economics, as we know it, was a choice, a construction to justify the capitalism that creates jobs that sell knives over the phone. (This is an oversimplification of no one specific theory; don’t @ me to complain.)

In the few years between the degree that helped me grow as a person and the degree that (barely) helped me get a career, I read a lot. This included a fair bit of the social philosophy writings of Bertrand Russell. In high school I read a lot of quotation books and some of his stood out to me at that time. When I read his actual essays, I was not disappointed. In Praise of Idleness, both the individual essay and the collection in a book of the same name, rang profoundly true for me. These were written in the 1920s and ‘30s, some during the Great Depression, and advocated the socialist ideals of working as necessary for society, and leisure as necessary for the self. It’s in contrast to the strict Protestant (and toxic) work ethic that, while drilled into me, I know is wrong. Idleness in this case isn’t laziness; it’s free time to pursue things for their own purpose. It was written before television and other technological tools to sedate overworked minds were in virtually every western home, so the idleness we think of because of that is very different from what Russell praised. He argued for genuinely free time.

Through my education and experiences, I know the 40 hour workweek is fake. I know it doesn’t improve the world. I know we could cut out entire sectors and still be happy as long as basic needs were guaranteed to be met—and I know we can do this, if only we shed the idea of needing to suffer through work to deserve this.

This whole time, climate change has been a known (and growing, holy shit) threat/reality, which has been especially frustrating to witness given obvious solutions. (I will not get into detail here of how it also relates to the pandemic, but it very much does.) This perspective made the word “degrowth” click with me immediately. It is ridiculous—beyond silly, just dire—how deeper we are digging for no benefit except richer rich at the expense of the planet. And degrowth is necessary to curb that.

We have been conditioned, as members of society, to be concerned with economic growth. Without economic growth comes consequences through policy that take things away from most of us to preserve what is already owned by the richer. We always need more jobs—not better jobs, not better wages or better hours or better things, just more jobs. We need higher profits that lead to more GDP. (This conflicts with needing more jobs as profits are made from not paying workers in proportion to the value they produce, but pay no mind to all the layoffs in all sectors.) We need “innovation” that changes how we do things, even if they have a negative impact on the earth and livelihoods of most people—even if they are a con that will only last as long as quarterly profits go up.

This is the direction we’re going in with capital at the helm; it is a sinking ship. This “growth” is speculation of a future that wouldn’t be able to maintain itself. Appliances and electronics are designed to break so they need to be replaced. We see planned obsolescence in our daily devices as these companies know they will have to sell phones or tablets or computers to us every couple of years to maximize their profits; thus any support or updates has an expiry date that puts our security at risk and makes us update to operating systems of declining privacy. We saw wealth-grabbing tech fads with cryptocurrency and we saw it with NFTs; we will undoubtedly see it with the large language models (LLMs) that are currently the hype. The latter technology takes up record-breaking amounts of energy and produces what humans are already capable of. It’s meant to replace creative professions because that is what people like to do, and rich people don’t profit off of poor people’s happiness (another essay; another day).

Degrowth is not a decline, because it is about abandoning the above and looking at quality over...well, not quantity, and not even novelty—it’s quality over greed. Degrowth is improvement in terms that matter to us all. A smart, loving, caring, healthy society values its people. Degrowth is not anti-technology, but it’s about useful and engaging and efficient technology instead. Degrowth of data mining, useless advertising, cheap products, and fast delivery will not eliminate the internet. If we embrace degrowth we won’t lose the tools we have. We can just use them to create what we want—what a 21st century Bertrand Russell would want to see us create—in our free time, with free minds. Change doesn’t come from boardrooms of shareholders, or economic measures acceptable to the profiting class. Art doesn’t come from sophisticated machines. Our lives aren’t made better by constantly replacing what we already have.

Nothing is going to improve if I buy steak knives over the phone.